by James Woodward

March 2024

Our lives are fragile, unpredictable and always deeply bound up with the unpredictable shapes of pain and grief. Even at our most complete and contented we live with the roars of fear, insecurity, regrets and limitations. Making sense of this and embracing the shapes and colours of living is a life long task. Perhaps only death completes them and us.

All of us have our stories to tell of these vulnerabilities. Even the most ordinary of uneventful lives have left us a little bit dented! We might take refuge in work or family or relationships investing in them by way of hoping they will bring us much longed for satisfaction. But the gaps and scars catch up. Life paints its picture onto the contours of our skin. This human stuff is what connects us across the generations transcending class, geography, race and gender. We are all in this amazing web of mess together. Shoulder to shoulder, with more in common with the stranger sat next to us than we know.

This is what makes us human. The mortal toils of living and loving and losing. What do you do with your boundedness? Who listens to your longings? Who understands the stuff inside that despite all best efforts refuses to be tamed? Perhaps the song writers can help us express that which remains hidden or unsaid?

Here is Nick Cave’s second verse of Into Your Arms –

Into my arms, O LordInto my arms, O LordInto my arms, O LordInto my arms

Faith, Hope and Carnage is a series of interviews with Cave and the journalist Seán O’Hagan. It is carefully transcribed and edited and offers this reader three immediate lessons about the ‘good’ life. First: pay attention to yourself. Second: search for questions that open doors and invite you to go deeper. Third, life is too short to be fake, tell it as it is however much it might hurt. Speak from within your heart.

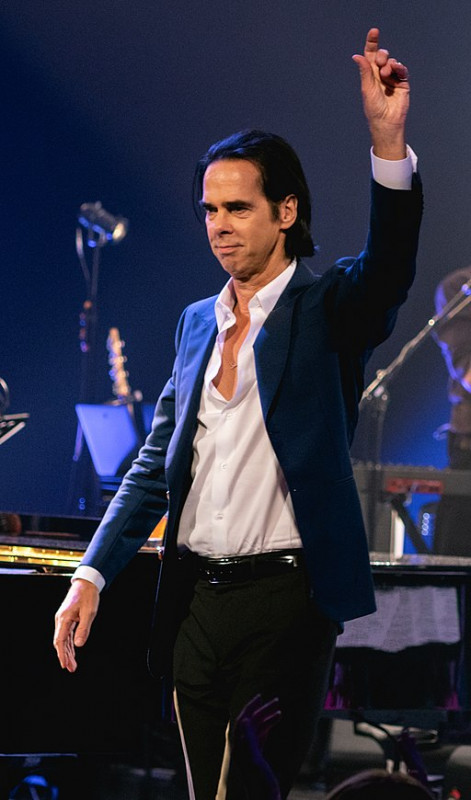

Cave is a legend. His music is a gift. In 2015 his life and his family were turned upside down by the death of his 15-year-old son, Arthur in Brighton. These conversations started with O’Hagan in the summer of 2020 and continued over lockdown. They cover a lot of his life. It is honest and has a texture that is deeply appealing. Cave wants to name stuff and especially his pain and grief. He is open and ruthless in his honest articulation of what faith might look like in the light of the carnage of death. He wants to know. He needs (perhaps) to trust another (and us) with his biography. He is unafraid of questions and the challenges of emotional turmoil.

We learn about how rock stars are made and unmade. His roots in the Potteries, childhood, drugs, addiction, and the connections and ruptures of making music with others. Rock and Roll captures the energy and egos and the fireworks of the search for fame. We learn about the creative process, social media and woke culture. Cave is as wise as he is honest.

Any reader half awake to their own losses in life especially loved ones will discover some rich (and painful) depths in the background music of grief that sticks to the pages and draws you in. Grief that is physical, present, unsettling, tear-making, uncontrollable and just hard work runs throughout this book. Grief takes physical shape as it rushes through the body and screams its pain. Cave wants to speak about it and invites us into the story which is both his and ours. The alternative is deadly. When we remain silent we imprison our lives in the company of the dead.

This book made me cry. The description of the detail of what happened the day his son died is harrowing and agonising. Cave needed to tell O’Hagan and we need to hear this song of love and heartache as it may echo fragments of our own. But loss and pain do not have the final word – there is hope and beauty and colour and life to these revelations. There is also deeply authentic theology.

And there is a message for those of us who theologise about God, Life and death. Cave describes the album Ghosteen as –

“a record that feels as if it came from a place beyond me and is expressing something ineffable. [Perhaps] God is the trauma itself. . . perhaps grief can be seen as a kind of exalted state where the person who is grieving is the closest they will ever be to the fundamental essence of things.”

Compare this theological wisdom to the present preoccupations in the playground of narratives and anxious preoccupations of the Church. For those really interested in paying attention, to noticing what people are living with, then read and reread these pages. Mission and new knowledge of God start with these essentials. What kind of human authenticity are we inviting people into? What is our story? How might grief be the gateway to hope in the carnage?

A book I shall read again. O’Hagan is a skilled listener and container for Cave’s fragilities and ours.

I will leave you with a link to my favourite Cave track.

======================

This review of Faith, Hope, and Carnage is adapted from the original on James Woodward’s website

Thank you for sharing this James. A timely and hopeful message for us as a family but I hope for the wider Church too as we transition through what you described at the \’grassroots theology\’ day in Ilminster last year. . . the possible death of an institution.