by Susan Francis

The Theology, Imagination and Culture masters degree (MATIC) at Sarum College is one of just a small handful of academic courses in the country which take on the complex but fruitful crossover of theology, imagination, and culture. As both a practicing artist, and someone with a personal history of involvement in faith organisations, it seemed to offer a much-needed platform to bring these two areas together, in perhaps more rigorous conversation than had previously been possible. What follows is a brief exploration into the realities of this endeavour. As I attempt to unwrap the nature of this experience, I will conclude by asking, where is the ‘here’ of now, compared to the ‘there’ of beginning, in other words, having set out on the MATIC path, where do I now find myself in terms of my faith, my relationship with art, and my commitment to furthering the dialogue between the disciplines of art and theology.

In his 1938 essay The Origin of the work of Art, the German philosopher Martin Heidegger said that artworks took the viewer from one place to another, that as the viewer approached the artwork they were transported, not simply to the image in front of them, but to a place of meaning beyond.(1) The American theologian Sallie McFague uses a similar turn of phrase when she writes about ‘God’s word, that strange truth that disrupts our ordinary world and moves us – and it – to a new place’.(2) To contemporary writer Jonathan Anderson, art and theology are ‘two lines of a railway track’ (3). All in all, it’s not difficult to see why art and theology might be so deeply entangled. Each seeks to move us to unchartered territory.

But not everyone wants to go on such a journey. In fact, both art and faith can often result in just the opposite – a digging in of heels if you like, a reinforcement of boundaries, a calcifying of ideas. While discussing public sculpture recently in my role as curator, one group participant was heard to say, ‘I don’t like art I don’t understand.’ Similarly, across all faiths, there will be people who will rigidly adhere to immovable doctrine, to the repetition of centuries-old traditions where they know exactly where they are and are comfortable residing there.

Thankfully, in the broad denominational offer, there is room for all persuasions, but it’s safe to say, that, when deciding to undertake the MATIC degree, one had better be up for the journey. Sitting in the small MATIC office discussing the possibility of applying for the course in 2018, the then course leader, Rev. Colin Greene, warned that such study may well disrupt one’s concept of faith. ‘Too late’ I replied, reflecting on some recent turbulent years leading up to this point, ‘it is already disrupted.’

One thing which seemed to unite all of the MATIC students was a need to question, to open up, to explore, to expand our edges and our boundaries. As the months went on, with a broad, challenging but rich programme of cultural, theological, and philosophical study, this was more than satisfied. With room for each student to follow their own area of fascination, I was drawn deeply into the liminal and ambiguous workings of the imagination inherent in the art experience. ‘Experience’ or ‘Erfahrung’ as the German translates, derives its etymological roots from the word ‘travel’, which might explain the particular capacity of German philosophers and theologians such as Hans Georg Gadamer and Paul Tillich to grasp the mobility inherent in the art experience.

But Sarum College delivers a uniquely potent and multi-layered pedagogical mix, for not only do its students learn through academic study, they learn through real life exchange. When lectures conclude for lunch or coffee breaks, rather than take to individual spaces, students come together to discuss over shared meals and refreshments, in welcoming communal areas, where one might be in conversation with a jazz singer seated on one side, and a Benedictine monk on the other. All of this rich diversity cleverly nurtures a listening environment of tolerance and inclusion, which is useful when study can cover anything from the transcendentals of beauty, truth and harmony, to Lady Gaga, Sex robots, AI and the path of global consumerism.

And so, to conclude my experience, as I unpack the nature of this journey I ask, where is the ‘here’ of now, compared to the ‘there’ of beginning? Where has this period of study taken me? While movement has undoubtedly taken place, it has cemented my view that as far as art, theology and faith are concerned, the journey is far from teleological. There is no definitive goal, no captured knowledge which answers all enquiry. In former Archbishop Rowan Williams words, the creative process ‘opens up what we did not understand and perhaps will not fully understand’.(4) We need to resist calcification, to continue moving, circling, overlapping within the conversation, to ‘keep the references circulating and be wary of them coming to a halt’ (5) as Bruno Latour reminded us. Art, I believe, provides a particularly inclusive, and non-binary space to do this. And while the church faces the challenge of speaking to a pandemic altered, war torn, multifaith, no faith and identity fluid 21st century society, it may find that contemporary art, and not just that which has been safely filtered for our sacred spaces, but the full breadth of contemporary art, in all its rawness, affords a rich and authentic space through which to do so.

+++

Susan Francis is a multidisciplinary artist, curator and writer creating object, installation, film and drawing which explores our lived experience as both analogue and digital selves. She is curator at Chapel Arts Studios, a socially-engaged, contemporary visual arts organisation which supports artists and delivers creative education in the North Hampshire region.

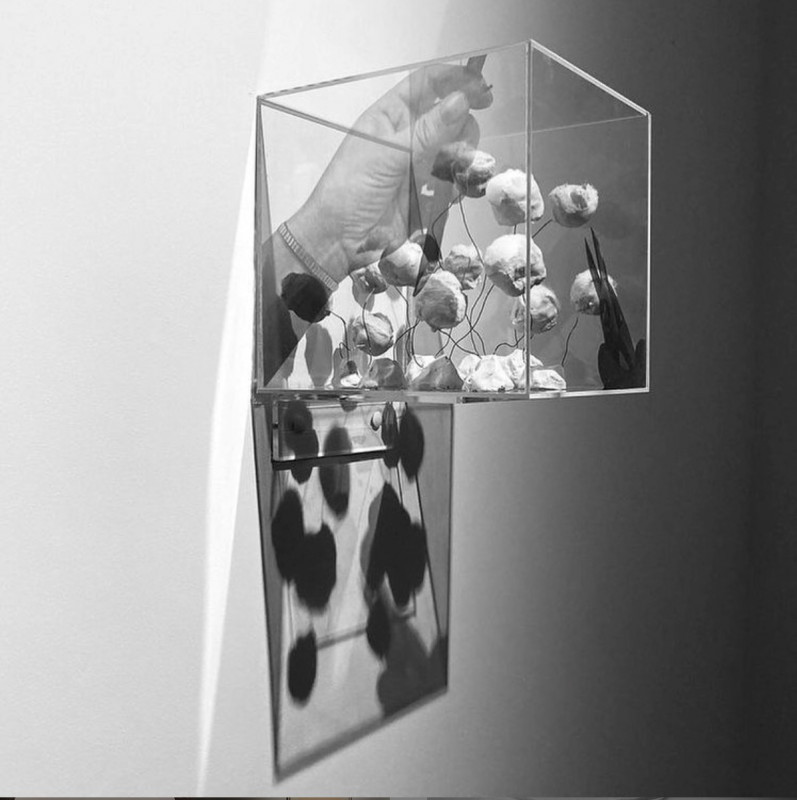

The art pictured here are works Susan has made since embarking on her MA.

Nothing is Nothing (2022) – cover image

Vibrant Cultivars (2020) – top left

The Holy Family (2018) – bottom right

Susan writes an occasional blog about the intersection of art, theology and philosophy called Tending the Borders

===========

Notes

- Martin Heidegger, Poetry, Language, Thought, 3rd edn, (New York: Harper and Row, 2001).

- Sallie McFague, Speaking in Parables: A Study in Metaphor and Theology, 2nd ed. (London SCM Canterbury Press, 2002)p32William D. Melaney, ‘Art as a Form of Negative Dialectics: “Theory” in Adorno’s Aesthetic Theory’, The Journal of Speculative Philosophy, 11.No:1 (1997), p40–52.

- Sounding the Depths, Theology through the Arts, ed. Jeremy Begbie (London: SCM Press, 2002), p164.

- Begbie, p28.

- Reader, Theology and New Materialism, p11.

Leave a Reply