August 2022

by The Very Revd Hugh Dickinson

Hugh Dickinson

On my next birthday I will be 93 years old. But my present intuition leads me to think that while I may live to see my next birthday, I will not be here to celebrate Christmas.

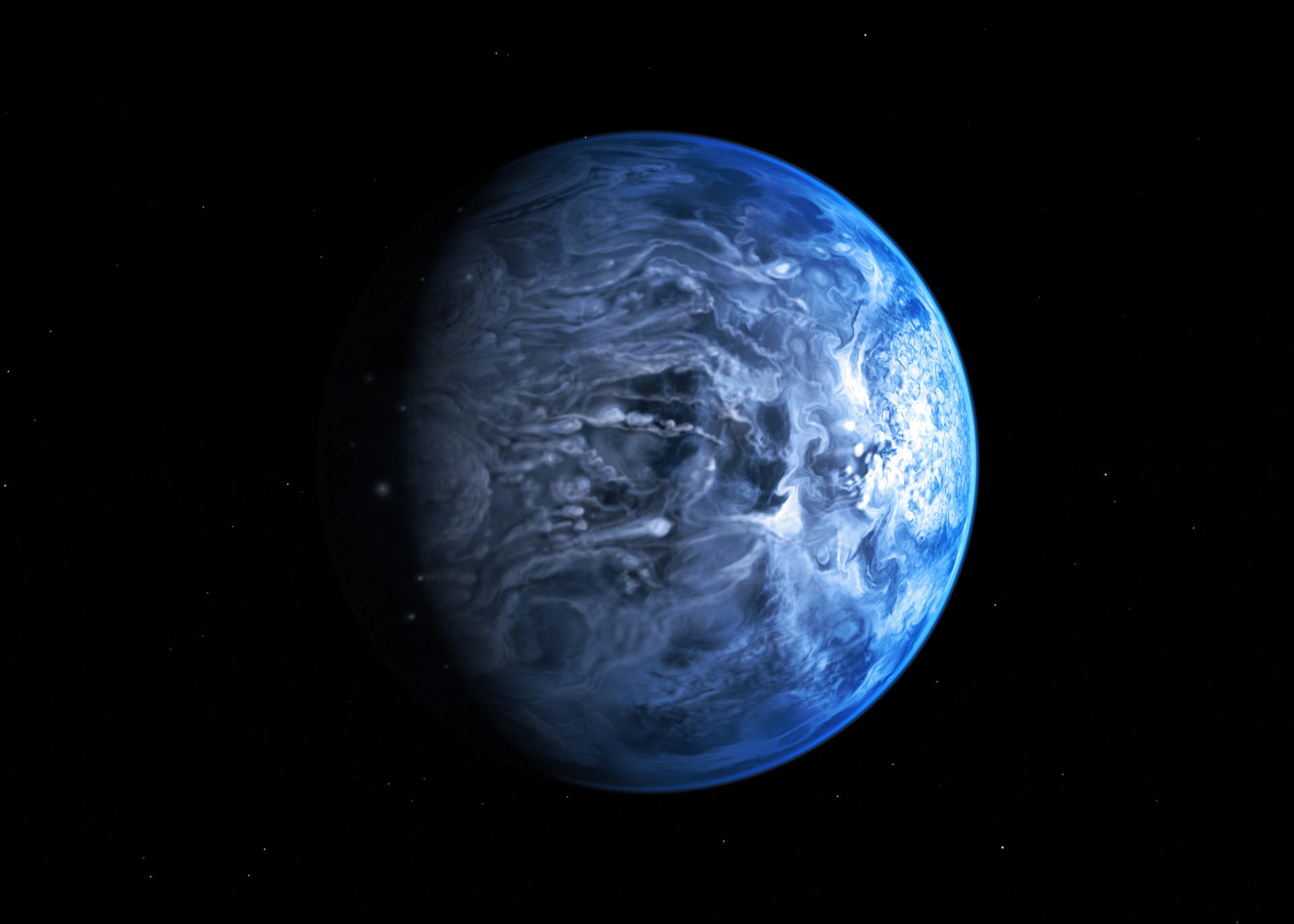

I am not afraid of death, though I am afraid of dying. Isaiah writes of the “shroud which is over all the nations, the fear of death.” This sense of the biological inevitability of our individual deaths is universal, but in this year 2022 there is a much darker cloud shrouding our planet, a terminal global catastrophe. If global warming is nor halted or reversed in the next 50 years, human civilisation as we know it may be impossible. It is conceivable that a small remnant of humankind will survive at the Poles, but the more likely prognosis is that a few primitive species will endure, perhaps some deep sea shrimps in the super-heated vents of abyssal volcanic vents, or blind moles in underground caves and cockroaches of course. In addition to this looming environmental Armageddon there are natural disasters like plagues, famines and forest fires, and also political and social unrest, civil catastrophes in which millions of people will perish in sub-Saharan Africa, Russia, the Americas, and possibly global war between China and the USA. Yes, there is a shroud over the future.

I have lived my life in nominally “Christian” or post-Christian cultures, which have provided me with a coherent world view, a narrative which has helped me to “make sense” of life as I have experienced it myself and of life on earth as modern science and historical research have begun to reveal how things have been on the universal scale of astrophysics and in the more domestic setting of life on earth over the past nine hundred million years. In this cosmic arena there are many mysteries which are gathered under the general heading of metaphysics — philosophical questions which have perplexed the minds of thoughtful men and women in different cultures and mystical traditions for thousands of years: Why does anything exist? What is Life? Why does time only flow one way? Why is the world so neatly constituted by mathematical logic? Where do “foundational” values come from, values so precious to our well-being, the Good, Truth, Beauty, the Sacred or Holy, altruistic and ecstatic Love, none of which can plausibly be attributed entirely to biological utilitarian causes. (What are the genes for the Taj Mahal?)

Then there is the whole realm of personal experience, realities which cannot be verified by rationalist or scientific methods, and are beyond the apprehension (or comprehension) of rational analysis or verbal description, yet are the stuff of life. This realm of foundational values is the garden in which the great religions plough and plant and feed their souls. All religions have intuitions of transcendence. Christianity is a religion which most explicitly speaks of life beyond death, although others do certainly know of it implicitly as is evidenced even by Stonehenge.

Although the Christian Creeds and its doctrines offer formal definitions of its beliefs it is not in its formularies but in its praxis, its liturgies, music, ceremonials and social relationships which invite personal participation.

Christendom has also opened windows into multicultural literatures and arts of which we yet have understood only a part. Nevertheless this religion has claimed the right to pronounce on the destiny of the whole, of all times, all places, of all existing things, because at the heart of this faith is the self-revelation of the universal Creator Spirit, the One who also holds the empty abyss out of which the Big Bang expanded 13,000,000 million years ago, when there was no “where” and no “when”. There is no future and no past, only the assurance that at the heart of this universal mystery there is unconditional love.

We can only speak confidently of a “future life” if we have had some personal encounter with the Creator Spirit and know in our bones an experience of being enfolded in a love as self-authenticating as a Schubert Quintet. At the centre of this encounter is an Agent who reaches out to touch our souls with an attractive field of force, a personal love which evokes in us a responding and transforming echoing love. It is Love with a Promise. Not a statement or verbal proposal but an embrace, which prompts me to embrace others, not just dear friends and acquaintances but strangers and aliens too. Nihil humanum alienum a me puto.

I want to draw them close to me because I have been held close by the Divine Love, and that action is so simply joyous that I find it difficult to hold myself back from enveloping others in my arms. I know that the One who holds me in his arms will never let go of me or let me go. And that goes for everyone I love.

Julian of Norwich hears Jesus telling her from the Cross, “This is how much I love you!” But it is from the torturing Cross that he speaks to her. Human beings are capable of doing such grotesquely cruel and wicked things to each other that any talk of unconditional love seems grotesquely absurd. And now clearly the most grotesque wickedness is our wilful destruction of this blue planet and all its miraculous life forms and our own civilisation. There is something wicked in us. Homo homini vulpus.

So as our world goes up in flames while men, women and beautiful children, so many of our fellow human beings and creatures are wiped from the face of the earth, what possible prayers can we bring to the feet of our Creator God? Only his own prayer, Eloi, Eloi, Lama sabachthani? That is the only prayer our ancestors could pray for so many centuries on the ravaged battle fields of two millennia of human conflict, and in the cemeteries and village churchyards of so many generations, and now on the cliff edge of our planet’s final years. Eloi Eloi.

Yet if it should be that among the conurbations of the sky there are other conscious moral beings who have known the touch and summoning of the the Creator’s love, they too will have felt the gravitational pull in their brief day and final night, all those unimaginable numbers of souls, more unimaginable than all the unimaginable myriads of stars, they too surely will be be gathered into the enfolding mystery of God.

+++

The Very Revd Hugh Dickinson was Dean of Salisbury Cathedral from 1986 until his retirement in 1996. Through his leadership and vision, governors and trustees founded Sarum College in 1995, a year after the closure of Salisbury & Wells Theological College. The photo of Hugh was taken during his address to mark Sarum College’s 20th Anniversary in September 2015 (ashmills.com).

Leave a Reply