10 August 2022

Sarum College has offered postgraduate studies in Christian Spirituality since 1999. Over 20 plus years, it continues to attract a wide variety of learners who are supported by our brilliant teaching team.

The programme is led by Dr Michael Hahn whose main specialisms are medieval spirituality, the Franciscans, and the development of mystical theology. His forthcoming book is, Bonaventure, Angela of Foligno and Late Medieval Mystical Theologies.

Dr Hahn will teach on several forthcoming courses, including:

- Inspiration and Imagination: Creative Expressions of the Spiritual Life (5-8 Sept 2022)

- Foundations and Forms of Christian Spirituality (10-13 Oct 2022)

- Clare of Assisi and the ‘Other’ Franciscan Female Theologians (19 Oct 2022)

- Western Christian Mysticism (24-27 April 2023)

Reading the work of medieval scholars reminds me why there is a growing interest in this period.

In her book Hidden Hands: The Lives of Manuscripts and Their Makers, Mary Wellesley uses the skill of a scholar’s pen and careful eye to open up the world of medieval manuscripts to a general reader without compromising the detail of her learning and scholarship.

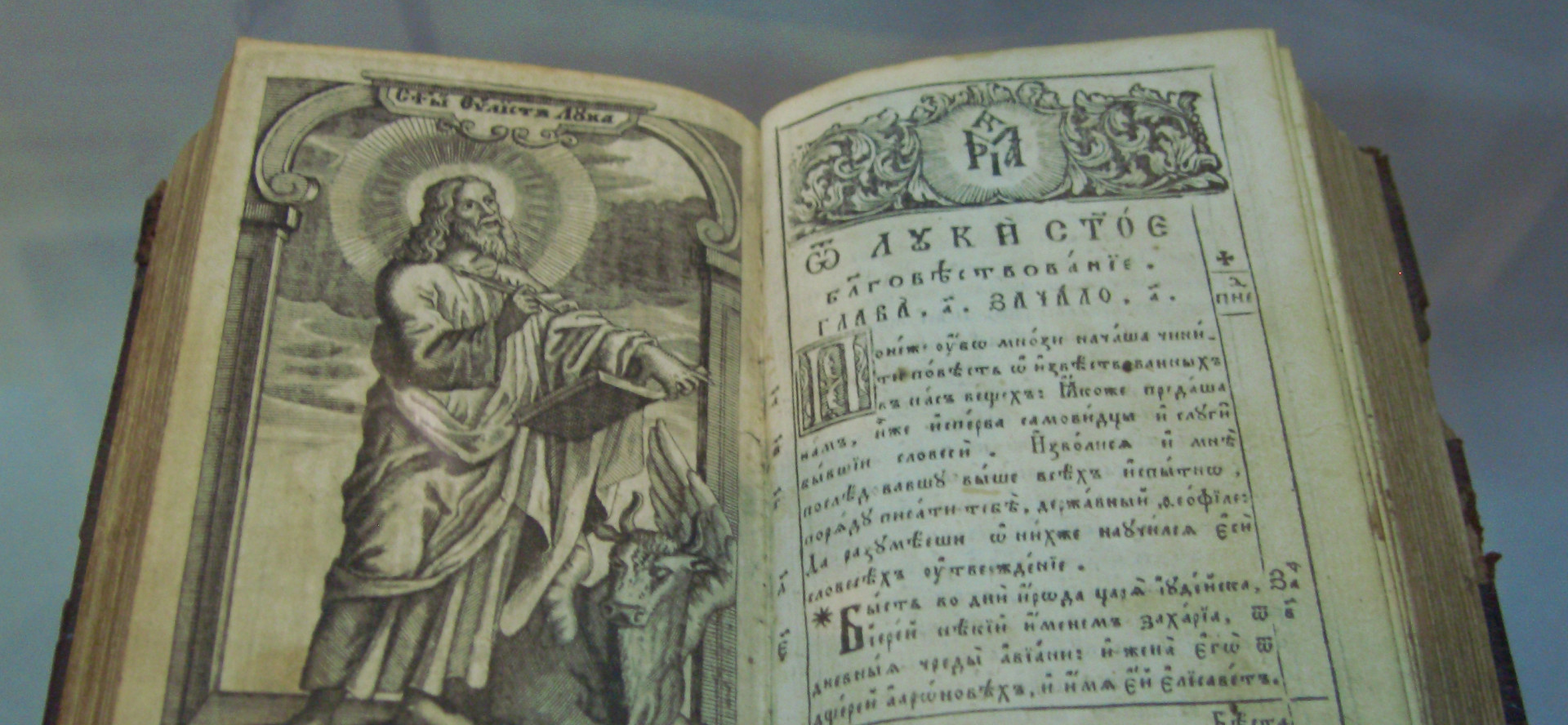

She takes one aspect of medieval life – the transmission of texts and stories through manuscripts — to show her reader how much life we glimpse in the story of making beautiful (but fragile) objects. They are the substance of our history and the body of knowledge that we pass on. Wellesley shows how culture, story, truth, history, politics and art have been relayed through the ages.

In the Prologue, the reader is taken into the production of parchment from the animal hide – a process she calls alchemy. Through her visit to William Cowley – the only remaining parchment maker in the UK — we learn about hidden manuscripts are found in unexpected places and how priceless labour is lost to theft or fire.

Subsequent chapters narrate the stories of the artisans, artists, scribes and readers, patrons and collectors who made and kept these delicate objects that have survived the ravages of fire, water and deliberate destruction to form a picture of both English culture and the wider European culture of which it is part.

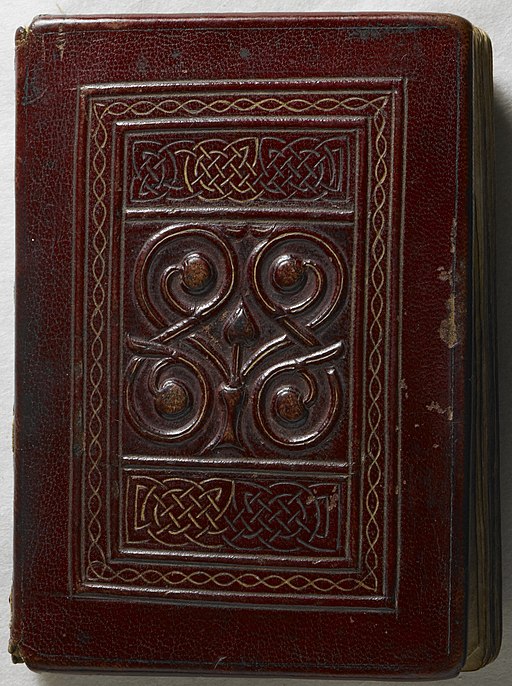

My favourite story explores the journey of the Cuthbert Bible (pp30-39).

The journey of this oldest surviving and earliest intact book in Europe is fascinating in itself. Marauding wars, the dissolution of the monasteries during the Reformation, see the book being passed on and on for interest and possibly safekeeping. It is now kept in the British Libraries Treasures gallery and periodically travels to Durham. It is so slight and its binding design so relatively simple that it is hard to believe that this manuscript was made 1,300 years ago and yet continues to speak to us across the centuries. It captures a sense of England especially in the early days of Christianity.

The journey of this oldest surviving and earliest intact book in Europe is fascinating in itself. Marauding wars, the dissolution of the monasteries during the Reformation, see the book being passed on and on for interest and possibly safekeeping. It is now kept in the British Libraries Treasures gallery and periodically travels to Durham. It is so slight and its binding design so relatively simple that it is hard to believe that this manuscript was made 1,300 years ago and yet continues to speak to us across the centuries. It captures a sense of England especially in the early days of Christianity.

Perhaps this volume is a timely reminder of the importance of nurturing a historical perspective on our present values and worldview. We need to look at history to learn from it. We need to delve into history in order to understand the endeavours and achievements of previous generations. Perhaps history can also help illuminate our present context and human struggles? In an age of information overload and a certain superficiality of knowledge, might learning to dig deep into the experience of previous generations and their gift to us give pause to consider the present in a new light?

All knowledge is partial and subject to bias. We are not made immortal by books and writing – the learning may confer truth that helps us to live well. Compilers, translators and transformers can mutilate the meaning of the author. Writing is subjective. ‘Each new form of an author’s work creates a new set of meanings in different ages and cultural contexts’ writes Wellesley (p280), reminding us that the way we understand the past is susceptible to bias. However these manuscripts which are brought alive in this book reveal a range of people who we might not otherwise in counter. These pages of story, reflection, accounts are important because they help us to access something of the lives of others from which we have much to learn.

One final ‘gift’ from the book. I was enthralled by the story of Julian of Norwich (pp240-249) in the context of the ‘religious life’ in England and the number of anchorites called to solitary life of prayer at this time. Within this vocational calling there is much wisdom. How do we live with the conflicted self? What needs to be named about about our human condition today? Has the pandemic taught us anything new about ourselves and how we might want to spend our time? We may be ambivalent about religion but can we feel the spiritual pulse that yearns and longs for something better from a different world and life? Where might we find rest and hope? Are we able to listen to our spiritual learning and yearning? Where is truth to be found about our human condition? Who will give us ‘new shewings’ that reveal what life might be within the context of our own limitations and contradictions?

A great start to holiday reading. What next?

Back to Sarum College: take a look at our learning offer in Christian Spirituality to see where learning and reading might take you this year.

Contact us to make an appointment (maadministrator@sarum.ac.uk) or join a Taster session. The next one is 14 November 2022

This piece was adapted from a review by The Revd Canon Professor James Woodward.

Leave a Reply