February 2024

by The Revd Canon Professor James Woodward

I believe that I may have had at least two copies of this book written by Rod Hacking (now a neighbour in Salisbury but then an incumbent in rural Ely) and published by Mowbray in 1988. What happened to them I know not – beware of lending books, they have a habit of not returning! This copy was a bargain 50p in a local charity shop.

You will note my delight and stimulation in reading this during a wet Welsh day, while on a few days escape, by the yellow markers in the book below.

Gilbert Shaw was closely associated with the Community of the Sisters of the Love of God for the final 10 years of his life. He became the Sisters’ retreat conductor first, then teacher, and finally their Warden in 1963. My own interest in the book was our shared knowledge of the convent, Fairacres, as I have had a connection with the Community since my university days in the late 1970s.

The book makes other connections too which brought back happy memories. Shaw was married in St Saviour’s Pimlico where I lodged in my final year as student in 1982. He lived in St Alphege Clergy House (off the Blackfriars Bridge Road) where I lodged at the end of my first year at Kings London. I was transported back to Bede House in Kent and Boxmoor in Hemel Hempstead, both daughter Houses of the Fairacres Convent in Oxford, where I spent a little time living alongside the Sisters.

Then there are the names of influences and encouragers: Mother Jane, Fr Percy Coleman, Fr Ken Leech and the wonderful Fr Donald Allchin who admitted me as a priest associate of the community in 1989. How naming places and people can open the gates memory and of gratitude.

Hacking narrates this life with care informed by a variety of voices and sources. He is unafraid to make judgements especially in the private and sensitive area of Fr Shaw’s marriage. The chapters are theologically informed and he allows the voice of Shaw to shape our sense of the man, his wisdom and gifts together with his charism and growth in older age.

It is an important story which charts some of the growth and developments in the religious life during the twentieth century especially in the nurture of the Carmelite traditions of contemplation and the solitary life. It gives us a picture of the strength of the Anglo Catholic movement and its commitment to social justice in areas of deprivation and need. It shows to our modern mindset something of the nature of sacrifice and work that is held by a rigorous discipline of prayer and devotion.

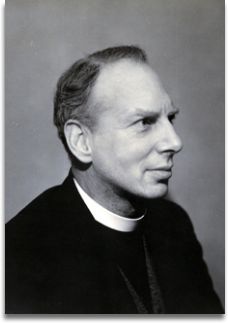

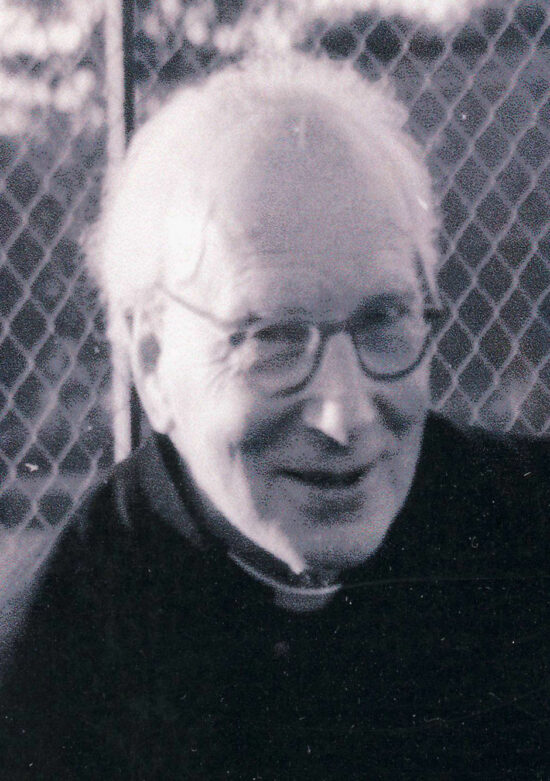

There is another significant element in the biography which is intriguing from both a professional and personal perspective. In eighteen months or so I shall mark the fortieth anniversary of my ordination in Durham Cathedral. A number of friends and colleagues have asked when I might be retiring. It is an interesting question that is not always asked out of benevolent curiosity! These two pictures show Shaw some decades apart!

The latter is taken in Oxford towards the end of his life. Shaw’s work was lifelong and Hacking suggests that some of his more generative work took place in his final decades. His ministry of prayer, teaching, presence and direction found a focus and depth towards the end of his life. Hacking describes this chapter seven as Living in the Light at the End 1964-1967.

The latter is taken in Oxford towards the end of his life. Shaw’s work was lifelong and Hacking suggests that some of his more generative work took place in his final decades. His ministry of prayer, teaching, presence and direction found a focus and depth towards the end of his life. Hacking describes this chapter seven as Living in the Light at the End 1964-1967.

Shaw makes a plea to the community for a rediscovery of our need for self loss. At the heart of the vocation, he argued, the community is and should be in conflict with self at the deepest levels of their being. He set his words in the context of the failure and collapse of the Church in the 1960s, a period which Shaw characterised as ‘these dark days.’

The contemplative must choose the way of prayer as a process of self-stripping, and the battle with self which sent Antony and many others in the desert. This invocation to a radical spirit is set against the prevailing anxiety of modernity. True then and certainly much needed today!

For Shaw this was a passionate invitation to a deeper contemplation where there was a total commitment to prayer. This was obedience, attentiveness to scripture and a nurture of an awareness of the heart and presence of God in the natural world. His heartfelt plea was to live within the truth of letting God do what God wants with ‘each one of you, and not what you want.’

Shaw shows us the value of these latter years of mature Christian living. Older age is today so marginalised and undervalued by our anxious hyperactivity. We see in this time with the Community that it forged for Shaw an articulation of the radical shape of our discipleship.

It may have been that it was only in these last couple of years of his life that he was finally able to say exactly what he needed. The wisdom of age has a unique spiritual charism and gift.

Nearly 40 years later, there is an agency and prophecy here about some of our inhabiting what it means to follow Christ. We need to go deeper and allow our activism to be shaped by contemplation. We should also be much more confident about the theological tradition, and its infinite ability to yield wisdom for our journey. The best may yet be to come.

Hacking tell us of Shaw’s embrace of his death as he shared this with Donald Allchin: “you know, Donald, we’ve spoken so much about theology, but in the end what matters above all is Love”. This simple and moving appeal to the heart is the “work” of a lifetime of discipline and struggle – perhaps best characterised by his teaching – living in the light of the end.

Persistence, discipline, judgement, and love combined in the way Shaw gave voice to what he knew of the love of God in his heart and head.

Some of Gilbert Shaw’s teaching are captured on a Fairacres Card from their Printing Press and one of which I treasure in my copy of SLG Rule given to me by Mother Jane.

The Holy Spirit will never give you stuff on a plate – you’ve got to work for it.

Your work is listening – taking the situation you’re in and holding it in courage, not being beaten down by it.

Your work is standing – holding things without being deflected by your own desires or the desires of other people round you. Then things work out just through patience. How things alter we don’t know, but the situation alters.There must be dialogue in patience and charity – then something seems to turn up that wasn’t there before.

We must take people as they are and where they are – not going too far ahead or too fast for them, but listening to their needs and supporting them in their following.

The Holy Spirit brings things new and old out of the treasure.

Intercessors bring the ‘deaf and dumb’ to Christ, that is their part.

Seek for points of unity and stand on those rather than on principles.

Have the patience that refuses to be pushed out; the patience that refuses to be disillusioned. There must be dialogue – or there will be no development.

I have appreciated this insight into the faithful life of Gilbert Shaw. It is an area that deserves further work and reflection, perhaps alongside the work of Mother Mary Clare. I am glad and blessed by my connection with the community and much more than that, it is a gift to the Church.

_________________________________________________________

The Revd Canon Professor James Woodward is Principal of Sarum College. View his full bio

This article is adapted from a review of the book, Such a Long Journey: A biography of Gilbert Shaw, Priest, which appears on James Woodward’s own website

Discover ways to deepen your understanding of faith and spirituality

Learning opportunities in ministry

Learning opportunities in Spiritual Direction

Postgraduate study in Christian Spirituality

(The next free online Taster Day is 4 March)

Faith in a Time of Dementia – The Other Side of Nothingness (13 March 2024)

The Practice of Spiritual Care (13 May 2024)

Leave a Reply